Hard-core predicate

In cryptography, a hard-core predicate of a one-way function f is a predicate b (i.e., a function whose output is a single bit) which is easy to compute given x but is hard to compute given f(x). In formal terms, there is no probabilistic polynomial time algorithm that computes b(x) from f(x) with probability significantly greater than one half over random choice of x.[1]:34

A hard-core function can be defined similarly.

A hard-core predicate captures "in a concentrated sense" the hardness of inverting f.

While a one-way function is hard to invert, there are no guarantees about the feasibility of computing partial information about the preimage c from the image f(x). For instance, while RSA is conjectured to be a one-way function, the Jacobi symbol of the preimage can be easily computed from that of the image.[1]:121

It is clear that if a one-to-one function has a hard-core predicate, then it must be one way. Oded Goldreich and Leonid Levin (1989) showed how every one-way function can be trivially modified to obtain a one-way function that has a specific hard-core predicate.[2] Let f be a one-way function. Define

- g(x, r) = (f(x), r),

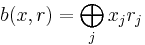

where the length of r is the same as that of x. Let  denote the jth bit of x and

denote the jth bit of x and  the jth bit of r. Then

the jth bit of r. Then

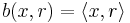

is a hard core predicate of g. Note that  where

where  denotes the standard inner product on the vector space

denotes the standard inner product on the vector space  . This predicate is hard-core due to computational issues; that is, it is not hard to compute because g(x, r) is information theoretically lossy. Rather, if an algorithm exists to compute this predicate efficiently, then an algorithm exists to invert f efficiently. A similar construction yields a hard-core function with log (|x|) output bits.

. This predicate is hard-core due to computational issues; that is, it is not hard to compute because g(x, r) is information theoretically lossy. Rather, if an algorithm exists to compute this predicate efficiently, then an algorithm exists to invert f efficiently. A similar construction yields a hard-core function with log (|x|) output bits.

It is sometimes the case that an actual bit of the input x is hard-core. For example, every single bit of inputs to the RSA function is a hard-core predicate of RSA and blocks of  bits of x are indistinguishable from random bit strings in polynomial time (under the assumption that the RSA function is hard to invert).[3]

bits of x are indistinguishable from random bit strings in polynomial time (under the assumption that the RSA function is hard to invert).[3]

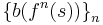

Hard-core predicates give a way to construct a pseudorandom generator from any one-way permutation. If b is a hard-core predicate of a one way function f, and s is a random seed, then

is a pseudorandom bit sequence.[1]:132

Hard-core predicates of trapdoor one-way permutations (known as trapdoor predicates) can be used to construct semantically secure public-key encryption schemes.[1]:129

See also

List-decoding (describes list decoding; the core of the Goldreich-Levin construction of hard-core predicates from one-way functions can be viewed as an algorithm for list-decoding the Hadamard code).

References

- ^ a b c d Goldwasser, S. and Bellare, M. "Lecture Notes on Cryptography". Summer course on cryptography, MIT, 1996-2001

- ^ O. Goldreich and L.A. Levin, A Hard-Core Predicate for all One-Way Functions, STOC 1989, pp25–32.

- ^ J. Håstad, M. Naslund, The Security of all RSA and Discrete Log Bits (2004): Journal of the ACM (JACM), 2004.

- Oded Goldreich, Foundations of Cryptography vol 1: Basic Tools, Cambridge University Press, 2001.